Introduction

The purpose of this field trip project was to practice measuring and interpreting stratigraphic sections1 while gaining hands-on experience with Cambrian2 sedimentary rocks in the Appalachian region. On April 13, 2025, we visited an outcrop near Walland, Tennessee (coordinates: N 35° 43’ 54.60”, W 85° 49’ 01.21”). The formation we studied is made up of Cambrian sandstones that closely resemble the Weverton Formation3, which is the base of the Chilhowee Group4. It is located at the western edge of the Blue Ridge physiographic province, where Chilhowee clastics overlie the Grenville basement. This sequence formed during the early Paleozoic period after the breakup of the supercontinent Rodinia5. Specifically, they were deposited in coastal and nearshore marine environments because of rising sea levels during the Sauk transgression6. The Sauk transgression was one of the most significant early Paleozoic sea-level rises recorded on Laurentia, in which the sea level rose relative to the land, causing water to flood previously dry continental areas.

Rodinia, which was the supercontinent built by the Grenville Orogeny7 around 1.1 to 0.9 billion years ago, included most of the world’s continental crust, like present-day Africa, South America, Laurentia, and more. By the late Proterozoic, Rodinia began to fracture, which created rifting along what became Laurentia’s eastern margin. During the Cambrian, Laurentia was located in the low to mid-southern paleolatitudes and later drifted northward. This placed what would become the Appalachian passive margin8 in a warm, tropical climate, at the time which was conducive for the deposition of carbonates and siliclastic sediments.

The breakup of Rodinia caused eruptions like the Catoctin volcanism, followed by rapid erosion of the Grenville highlands, which created space for siliclastic sediments to deposit. During the Sauk transgression, global sea level rose, and regional sinking led to pulses of marine flooding, progressively depositing the Chilhowee Group. This outcrop allows us to see these changes and therefore connect local sedimentary processes to the broader tectonic and depositional history of the Appalachian Basin.

Data Collection

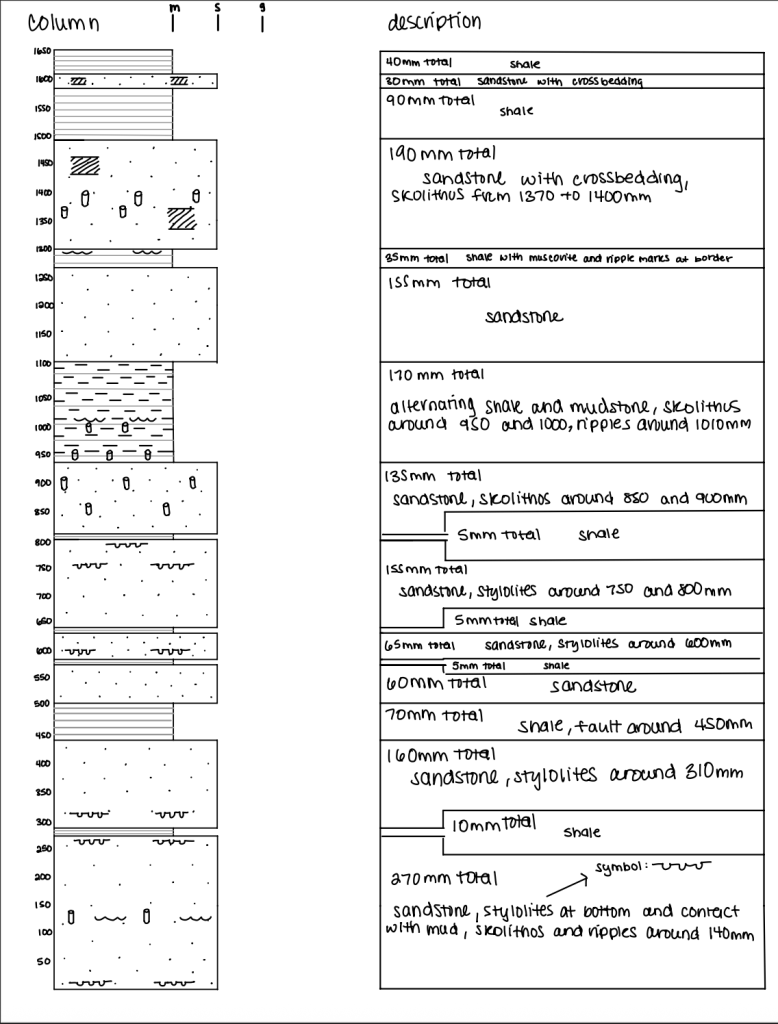

To collect our data, we used standard geological field tools and techniques, including a Jacob staff, hand lenses, and grain size cards. First, since the formation is significantly tilted, we identified sedimentary structures such as cross-bedding9 and ripple marks10 to determine the stratigraphic way up. These structures showed us that stratigraphic “up” was from right to left. This told us we needed to angle our Jacob staff about 30 degrees to the left from vertical to accurately measure the layers of this formation.

Using the Jacob staff, we measured the vertical thickness of each sedimentary layer from the bottom to the top. We calibrated the Jacob staff by having one person hold the staff and two other people stand back to ensure the staff was aligned with the formation. We then had the staff holder and one other person measure the layers, and the third person sketch a stratigraphic column. While measuring, we used hand lenses and grain size cards to examine and classify sediment textures, mineral compositions, and grain sizes. We also noted bedding styles, sedimentary structures, trace fossils, and lithology. Since the Jacob staff is 150 mm long, we did our measurements in sections of 150 mm, then moved to the left and aligned the staff with the section above the previous one, and continued doing this for the entire formation.

After measuring the formation, we examined some nearby fallen boulders, which allowed us to see features like fossil distribution, stylolites11, and sedimentary structures close up. All of this combined data allowed us to construct a measured stratigraphic column to show vertical changes through the formation.

Description and Interpretation

We first had to determine the stratigraphic way “up” because the outcrop is significantly tilted. Using sedimentary structures that indicate this, like cross-bedding and ripple marks, we confirmed that the stratigraphic “up” direction is right to left. The outcrop showed alternating layers of sandstone and mudstone/shale, with a distinctive trend where sandstone thickness gradually decreased upward, and the shale layers increased in thickness upward. In those layers, the clasts seemed to be moderately sorted and subrounded.

Throughout the section, we found sedimentary structures including ripple marks, cross-bedding, and the trace fossil Skolithos12, which is indicative of high-energy conditions found in nearshore marine environments. We also observed stylolites within several layers, showing post-depositional compaction due to burial pressure.

The main mineral we observed was quartz arenite13, characterized by predominantly quartz grains that seemed to be subrounded and moderately sorted. This indicates submature14 sedimentary conditions, which are typical of environments with moderate transport distances and energy conditions that result in partially round and moderately sorted sediment grains.

Combining all of these observations, we interpreted the depositional environment as shallow marine, likely influenced by tidal activity along a beach or shoreline. The alternating sandstone and mudstone layers suggest fluctuations in energy conditions, likely driven by tides or storms, which would deposit sand during high-energy periods and finer sediment during lower energy periods. This interpretation is further supported by the presence of Skolithos trace fossils since they are primarily found in well-oxygenated coastal environments, specifically the foreshore to shoreface transition zone.

A Skolithos I found on the trip (the white circles on the rock):

Discussion

This outcrop in Walland, Tennessee, is an amazing example of a Cambrian passive-margin sequence deposited shortly after Rodinia’s breakup. It is located within the Chilhowee Group, which includes environments from the Weverton Formation, the Harper’s Formation15, and the Antietam Formation16. The upward shift from coarse sandstone to finer mudstones suggests a transgressive facies17 sequence, showing a gradual shift from terrestrial to fully marine conditions during the Sauk transgression.

The Cambrian sands directly overlie the Swift Run Formation, which formed from the erosion of the Grenville highlands after the Catoctin flood-basalt event. This transition of volcanic rocks to immature terrestrial sediments, then to marine sands, shows how the landscape evolved from a rifted volcanic plateau into a passive continental margin. Beneath the Paleozoic sediments are the highly foliated Pedlar and Old Rag gneisses. That metamorphic foundation provided a lot of the sediment that eventually washed into the early Cambrian seas.

After Rodinia’s rifting, Laurentia’s eastern edge fell and flooded, allowing the Sauk Sea to transgress over basement and earlier deposits. The Chilhowee facies records this shoreline migration. Later, during the Late Paleozoic Alleghenian Orogeny18, the beds were folded, faulted, and some metamorphosed. Our field measurements of tilted bedding, stylolites, and minor fractures are evidence of those compressional forces as North America collided with Africa to build Pangea.

Putting this information and our field observations together, we see the transition from an active rift, through continental river deposits, to a passive-margin shelf. We also see the sea-level fluctuation from the upward-fining facies and trace fossils like Skolithos. Lastly, we see the later mountain building shown by the deformation features in otherwise sedimentary rocks. Overall, this roadcut acts as a small representation of nearly a billion years of Appalachian tectonics and sedimentation.

Conclusion

At this field trip in Walland, Tennessee, we practiced stratigraphic measurement and sedimentological interpretation on a Cambrian age passive margin sequence. Our measured section showed a trend of upward fining facies from sandstone to shale, indicating a transgressive shift from coastal to deeper marine conditions. More detailed observations revealed cross-bedding, ripple marks, Skolithos burrows, and quartz arenite, which allowed us to reconstruct the depositional environments and validate them with the Sauk transgression of the Chilhowee Group. By seeing that the Chilhowee sands overlie Swift Run fluvial19 gravels and Catoctin basalts, and that those units then sit on top of the Grenville basement, we were able to see the series of events that formed this outcrop. Starting with initial rift volcanism, then erosion and fluvial deposition, then marine transgression, and finally folding and faulting during the Alleghenian orogeny. This outcrop contains key features of the Appalachian geological history and links ancient tectonic collisions, supercontinent dynamics, sea-level changes, and mountain-building processes in one roadcut.

This is the stratigraphic column I made based on our measurements and observations:

Thank you so much for reading my project! If you enjoyed, check out this project: Exploring Bias in Fossil Sampling Methods! If you have any questions, please leave a comment. And don’t forget to subscribe!

Definitions:

- Stratigraphic section: A vertical “slice” through rock layers that shows their sequence, thickness, and characteristics, used to understand how environments changed over time. ↩︎

- Cambrian: A geological time period roughly 541–485 million years ago, when many marine animals first appeared and widespread shallow seas covered much of the continents. ↩︎

- Weverton Formation: The basal unit of the Chilhowee Group, made of coarse sandstones and conglomerates deposited near ancient river deltas and beaches. ↩︎

- Chilhowee Group: A stack of Cambrian rocks in the southern Appalachians that records a marine transgression, from fluvial sands up through beach and offshore muds. ↩︎

- Rodinia: A supercontinent assembled ~1.1–0.9 Ga during the Grenville Orogeny, later rifting apart to form the early Paleozoic ocean basins. ↩︎

- Sauk transgression: A major early Paleozoic sea-level rise that flooded continental margins worldwide, depositing the Chilhowee sedimentary sequence. ↩︎

- Grenville Orogeny: A mountain-building event ~1.3–1.0 Ga that welded together continental blocks to form Rodinia, leaving high-grade metamorphic “basement” rocks beneath the Appalachians. ↩︎

- Passive margin: The broad, tectonically quiet edge of a continent—far from plate boundaries, where thick piles of sediment accumulate as the crust slowly cools and sinks. ↩︎

- Cross-bedding: Slanted layers within a sedimentary bed formed as ripples or dunes migrate, preserving current directions in the rock. ↩︎

- Ripple marks: Small, wavy ridges on a sediment surface made by moving water or wind, which get preserved as fossils of past currents. ↩︎

- Stylolites: Jagged, interlocking seams in rock formed by pressure-solution during deep burial, often looking like dark “teeth.” ↩︎

- Skolithos: Vertical, tube-like burrows in sand made by marine worms or similar organisms, indicating a high-energy shoreline or foreshore environment. ↩︎

- Quartz arenite: A very pure sandstone composed almost entirely of well-rounded, well-sorted quartz grains, implying long transport or reworking. ↩︎

- Submature sediment: Sediment that’s partly well-sorted and rounded but still contains a mix of grain sizes or shapes, indicating moderate transport. ↩︎

- Harper’s Formation: A middle unit of the Chilhowee Group made of lagoonal and tidal-flat muds and siltstones, deposited in protected, shallow-water settings. ↩︎

- Antietam Formation: The upper unit of the Chilhowee Group, consisting of beach and nearshore sandstones that mark the peak of the Sauk Transgression. ↩︎

- Facies: A body of rock with distinctive characteristics (grain size, structures, fossils) that reflects a particular depositional environment—e.g., “transgressive facies sequence.” ↩︎

- Alleghenian Orogeny: The Late Paleozoic mountain-building event (~325–260 Ma) when Africa collided with North America to form Pangea, deforming earlier strata. ↩︎

- Fluvial: Pertaining to rivers and streams; fluvial sediments are those laid down by flowing water. ↩︎

Sources

NPS Shenandoah. (2015). Chilhowee metasedimentary rocks. Retrieved from link

NPS Catoctin. (2016). Geology. Retrieved from link

Tasistro-Hart, A. R., & Macdonald, F. A. (2023). Phanerozoic flooding of North America and the Great Unconformity. PNAS, 120(37), e2309084120. Retrieved from link

Gattuso, A. (2009). Tectonic significance of the Late Neoproterozoic Swift Run Formation and basement-cover unconformity in the Virginia Blue Ridge (Undergraduate thesis). College of William & Mary. Retrieved from link

Britannica. (n.d.). Alleghenian orogeny. Retrieved from link

Leave a comment