Abstract

The Paragon Formation, located on the eastern edge of the Cincinnati Arch in Kentucky, is well exposed at Big Hill within the Knobs Region of the Cumberland Plateau. This area is renowned for its fossil-rich shale layers, especially near Perry Lane. These layers contain a diverse array of fossils, including echinoderms, brachiopods, bryozoans, and corals. Recent discoveries of rare species, such as edrioasteroids and ophiuroids, highlight the formation’s paleoecological significance.

This study compares three fossil collection methods—random sampling, bulk sampling, and quadrant sampling—to evaluate their strengths and limitations. Random sampling is quick but relies heavily on the collector’s choices, often introducing significant bias. Bulk sampling provides a more comprehensive view of overall diversity but may over-represent common fossils in specific areas. Quadrant sampling offers consistent sampling areas, reducing some biases but still missing microhabitats or less-visible fossils.

Research on biases in fossil preservation and sampling shows that these factors can distort our understanding of past life. For example, studies on early land plants demonstrate how geological biases can exaggerate or misrepresent diversity patterns. For the Paragon Formation, we hypothesize that bulk and quadrant sampling will yield a more accurate picture of fossil diversity than random sampling. Addressing these biases is essential for reconstructing a clearer picture of ancient ecosystems.

Geological Setting

The Paragon Formation, an Upper Mississippian (Chesterian) unit, is a 60-meter sequence of shale, dolostone, and limestone located on the eastern flank of the Cincinnati Arch along the Cumberland Plateau margin. This formation is prominently exposed in Big Hill, Kentucky, within the Knobs Region, a landscape marked by hills capped with Pennsylvanian sandstones that create distinct erosional reliefs and extensive outcrops of underlying Mississippian rocks. As the uppermost Mississippian layer in this area of the Appalachian Basin, the Paragon Formation holds a rich array of fossils, including echinoderms, brachiopods, bryozoans, and corals, especially within the shale-dominated section near Perry Lane, Big Hill. Here, around 7 meters of shale, indicative of deep, muddy seafloor below wave interference, offer ideal conditions for paleoecological studies. Despite being a popular site, it still contains an abundant level of surface fossils, with recent discoveries revealing previously undocumented species such as edrioasteroids and ophiuroids.

Bias in the Geological Record

Random sampling is quick and provides a general sense of fossil presence in an area. However, collectors may favor larger or more visible fossils, and results can vary depending on who collects them and where they walk, potentially introducing bias into the findings. Bulk sampling involves collecting a large volume of material, which can provide a fuller picture of species diversity. Although this method reduces collector bias, it may be biased toward fossils that are abundant in the specific area sampled, rather than providing a comprehensive representation of the site’s diversity. Quadrant sampling uses a consistent sampling area, which helps to standardize collection. This method reduces both collector bias and the potential sampling area bias seen with bulk sampling. However, it may overlook microhabitats within the site.

A study on pterosaur disparity found that geological sampling biases significantly affect measurements of morphological diversity over time. Range-based disparity metrics, which can be compared to random sampling, were more influenced by sampling bias than other methods (Matin, et al., 2023). Another study on early land plant radiation showed that geological record biases, such as limited terrestrial sediments and uneven preservation, skewed the perceived timing and rate of early plant diversification, with certain events appearing exaggerated due to selective preservation and sampling (Capel, et al., 2023).

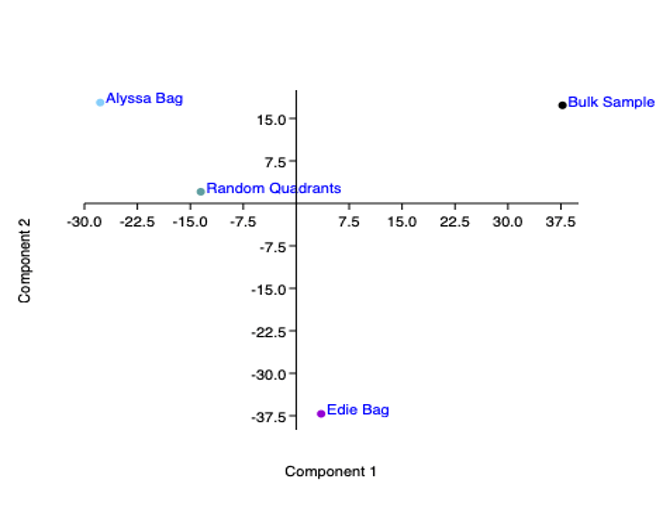

Of the different sampling methods used for this study, random sampling, bulk sampling, and quadrant sampling, we expect that the least biased methods are bulk and quadrant sampling. These methods allow for more systematic sampling, which should provide a more balanced view of diversity. In contrast, random sampling may miss certain fossils depending on what the collector sees and where they walk. This can be seen in Figure 1, which displays the differences in fossil types found using the different sampling methods.

Overall, sampling biases can distort our understanding of true biological diversity, making it essential to account for these biases when studying fossils.

Methods

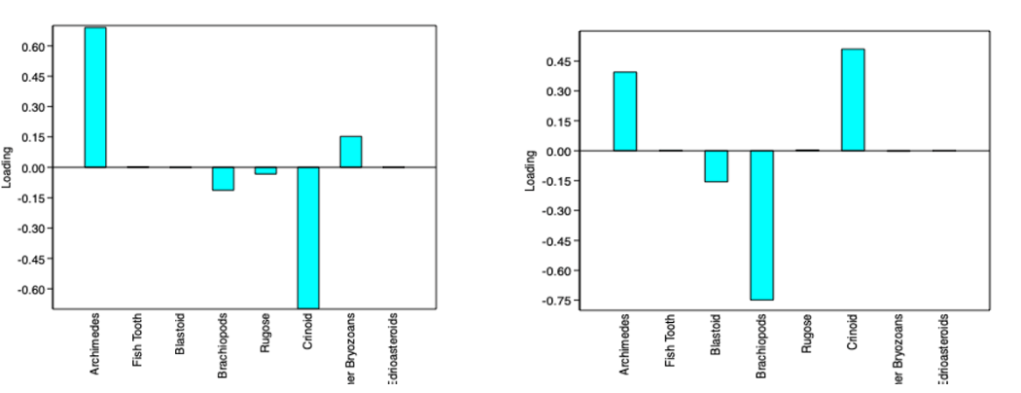

We sorted and counted fossils from each sample and recorded the counts in Excel. Using those counts, we created figures such as pie charts to compare the proportions of different fossil types and to illustrate the differences in fossil composition among the sampling methods. We used PAST software to further analyze the data, as shown in Figures 1 and 2. Our results were compared to the data from other research groups that used bulk and quadrant sampling to determine the best method for accurately representing the fossil record at this locality.

Case Study

Figures 3 and 4 show the results from the random sampling conducted by Alyssa and Edie, in which each participant was instructed to collect fossils randomly. Within these samples, we identified which fossil types were most abundant at this locality.

The limitations of random sampling are clear in our results, as biases toward certain fossils types is shown. Alyssa’s sample contained 81.7% crinoids, 8.2 % brachiopods, 32.1% crinoids, and 10.7% blastoids. These differences show inconsistency of random sampling and demonstrate its inability to accurately represent the fossil record at this site.

We also analyzed data from groups that used bulk and quadrant sampling. Quadrant sampling, while more systematic, still showed bias. For the quadrant data, crinoids made up 64.95% of the sample, while brachiopods made up 21.02%. This bias may be from only surface level fossils being collected or less dense fossils dispersing across the site. Bulk sampling provided a more balanced and accurate dataset in which it contained 48.49% Archimedes. This demonstrates that bulk sampling minimizes biases and offers a more clear picture of fossil abundance.

Our results confirm that random sampling is not the best method for understanding fossil diversity at this site. Both random and quadrant sampling are subject to significant biases, making bulk sampling the ideal approach for getting an accurate representation of the fossil record.

Figures

Figure 1: This is a principal component analysis (PCA) in PAST, where we are examining the relationship between different sample types based on fossil data. This plot shows how similar or different each sample (Alyssa Bag, Edie Bag, Random Quadrants, and Bulk Sample) is from the others based on their fossil contents. Bulk Sample (black point) is separated from the other samples along Component 1, suggesting that it contains a different composition of fossils compared to the other sampling methods. Alyssa Bag and Edie Bag (lighter blue and purple points) are clustered on the left side of Component 1, which indicates they might have similar fossil assemblages but differ slightly along Component 2. Random Quadrants (cyan point) is positioned closer to the center, suggesting it has a more balanced fossil composition relative to the other samples. This separation along the axes suggests that the different sampling methods (bulk sample versus random picking by individuals) might influence the types of fossils found or their abundance.

Figure 2: Component 1 and Component 2 (respectively) are the axes that capture the main patterns of variation among the samples, with Component 1 explaining the greatest amount of variation, followed by Component 2. The loading plots show how much each fossil group contributes to the separation along Component 1 and Component 2 in the PCA plot. For Component 1, Archimedes fossils have high positive loadings, while Crinoid fossils have high negative loadings, indicating that these fossil types are the primary contributors to the variation captured by Component 1. For Component 2, Crinoid fossils have high positive loadings, while Brachiopods have high negative loadings, making them the primary contributors to the variation along Component 2.

Sources

Martín, J.E., de Esteban-Trivigno, S., Vullo, R., & Jalil, N.E. (2023). How do geological sampling biases affect studies of morphological evolution in deep time? A case study of pterosaur disparity. Evolution, 77(5), 1479-1496. https://doi.org/10.1093/evolut/0147

Capel, E., Monnet, C., Cleal, C.J., Xue, J., Servais, T., & Cascales-Miñana, B. (2023). The effect of geological biases on our perception of early land plant radiation. Palaeontology, 66(2), e12644. https://doi.org/10.1111/pala.12644

And thanks to my project partner Lillian Sims

Leave a reply to Exploring Cambrian Seas in Walland, TN – Emily’s Biology Blog Cancel reply